[ad_1]

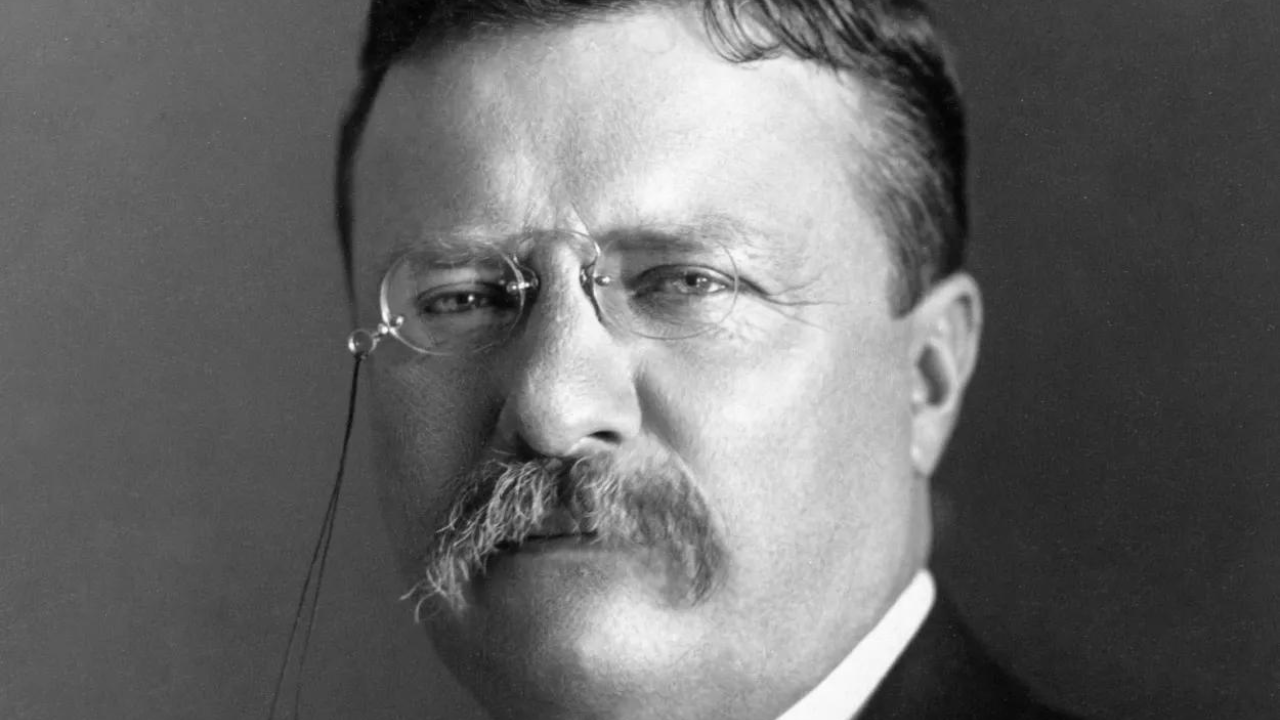

WASHINGTON: Donald Trump is not the first former president to survive an assassination attempt while trying to reclaim his old office. More than a century ago, Theodore Roosevelt was shot just before he was scheduled to go onstage at a campaign event — and went ahead to give his speech anyway with a bullet in his chest.

Roosevelt’s gritty response to the attack in 1912 proved to be the stuff of legends and helped cement his reputation for toughness.To that point in US history, three other presidents had been killed by assassins, including William McKinley, whose death elevated Roosevelt, then the vice president, to the presidency. But as of then, no current or former president had been shot without dying.

Roosevelt, like Trump, was staging a comeback attempt, running again four years after moving out of the White House. Unlike Trump, Roosevelt had left office voluntarily, declining to run in 1908 after serving nearly two terms. Instead, he had helped elect his protégé, William Howard Taft. But within four years, the two had a falling out and Roosevelt decided to challenge Taft for the presidency.

Although Taft beat him for the Republican nomination at the GOP convention, Roosevelt broke off from his old party to form the Progressive Party, also known as the Bull Moose Party, so that he could compete in the fall contest against Taft and Woodrow Wilson, the Democratic governor of New Jersey.

On October 14, 1912, Roosevelt was in Milwaukee, coincidentally the same city where Trump is scheduled to be nominated this week. As Roosevelt left the Gilpatrick Hotel to head to a nighttime speaking event, a man named John Schrank approached and opened fire with a Colt revolver. Several men tackled Schrank, but Roosevelt stopped the crowd from killing him on the spot.

Roosevelt, 53, was saved by a metal eyeglasses case and the fat text of his speech, 50 pages folded over so that it was 100 pages thick, in his pocket. But the bullet, even slowed down, still penetrated his chest and he found blood on his hand when he searched for and found a dime-sized wound. Allies wanted to take Roosevelt to the hospital, but he insisted on proceeding to the auditorium to deliver his address first. And thus followed one of the most extraordinary speeches in presidential campaign history.

“I don’t know whether you fully understand that I have just been shot,” Roosevelt told the astonished crowd as he got started. “But it takes more than that to kill a Bull Moose!”

He apologized that as a result he might not be able to speak as long as normal — and then proceeded to give a 90-minute stemwinder. Only at that point did he agree to be taken to the hospital. The bullet had been headed straight for his heart before stopping, lodged against a rib 4 inches from the sternum.

Schrank was what is today called a lone wolf, an individual acting outside of any network. When Roosevelt, just shot, asked him why he had done it, Schrank had “the dull-eyed, unmistakable expressionlessness of insanity,” as Edmund Morris put it in the final volume of his famous three-book account of Roosevelt’s life.

Schrank told authorities that he had had visions of the slain McKinley calling for Roosevelt’s death and he had thought that it was his responsibility to stop Roosevelt from breaking George Washington’s tradition of serving no more than two terms, long before the 22nd Amendment formally put the limit in the Constitution.

The attempt on his life “captured the imagination of the country,” H.W. Brands, a historian at the University of Texas at Austin, wrote in “T.R.,” another biography of the 26th president. But as impressive as Roosevelt’s performance that day had been, it did not propel him to victory. He finished ahead of Taft but, having split the Republican vote, was defeated by Wilson. Unlike a later president, Roosevelt conceded defeat. “Like all other good citizens,” he told reporters, “I accept the result with good humor and contentment.”

Roosevelt’s gritty response to the attack in 1912 proved to be the stuff of legends and helped cement his reputation for toughness.To that point in US history, three other presidents had been killed by assassins, including William McKinley, whose death elevated Roosevelt, then the vice president, to the presidency. But as of then, no current or former president had been shot without dying.

Roosevelt, like Trump, was staging a comeback attempt, running again four years after moving out of the White House. Unlike Trump, Roosevelt had left office voluntarily, declining to run in 1908 after serving nearly two terms. Instead, he had helped elect his protégé, William Howard Taft. But within four years, the two had a falling out and Roosevelt decided to challenge Taft for the presidency.

Although Taft beat him for the Republican nomination at the GOP convention, Roosevelt broke off from his old party to form the Progressive Party, also known as the Bull Moose Party, so that he could compete in the fall contest against Taft and Woodrow Wilson, the Democratic governor of New Jersey.

On October 14, 1912, Roosevelt was in Milwaukee, coincidentally the same city where Trump is scheduled to be nominated this week. As Roosevelt left the Gilpatrick Hotel to head to a nighttime speaking event, a man named John Schrank approached and opened fire with a Colt revolver. Several men tackled Schrank, but Roosevelt stopped the crowd from killing him on the spot.

Roosevelt, 53, was saved by a metal eyeglasses case and the fat text of his speech, 50 pages folded over so that it was 100 pages thick, in his pocket. But the bullet, even slowed down, still penetrated his chest and he found blood on his hand when he searched for and found a dime-sized wound. Allies wanted to take Roosevelt to the hospital, but he insisted on proceeding to the auditorium to deliver his address first. And thus followed one of the most extraordinary speeches in presidential campaign history.

“I don’t know whether you fully understand that I have just been shot,” Roosevelt told the astonished crowd as he got started. “But it takes more than that to kill a Bull Moose!”

He apologized that as a result he might not be able to speak as long as normal — and then proceeded to give a 90-minute stemwinder. Only at that point did he agree to be taken to the hospital. The bullet had been headed straight for his heart before stopping, lodged against a rib 4 inches from the sternum.

Schrank was what is today called a lone wolf, an individual acting outside of any network. When Roosevelt, just shot, asked him why he had done it, Schrank had “the dull-eyed, unmistakable expressionlessness of insanity,” as Edmund Morris put it in the final volume of his famous three-book account of Roosevelt’s life.

Schrank told authorities that he had had visions of the slain McKinley calling for Roosevelt’s death and he had thought that it was his responsibility to stop Roosevelt from breaking George Washington’s tradition of serving no more than two terms, long before the 22nd Amendment formally put the limit in the Constitution.

The attempt on his life “captured the imagination of the country,” H.W. Brands, a historian at the University of Texas at Austin, wrote in “T.R.,” another biography of the 26th president. But as impressive as Roosevelt’s performance that day had been, it did not propel him to victory. He finished ahead of Taft but, having split the Republican vote, was defeated by Wilson. Unlike a later president, Roosevelt conceded defeat. “Like all other good citizens,” he told reporters, “I accept the result with good humor and contentment.”

[ad_2]

Source link

830863 181257An intriguing discussion is worth comment. Im positive which you just write regarding this topic, could possibly not be considered a taboo topic but typically persons are too small to communicate on such topics. To another. Cheers 44673