[ad_1]

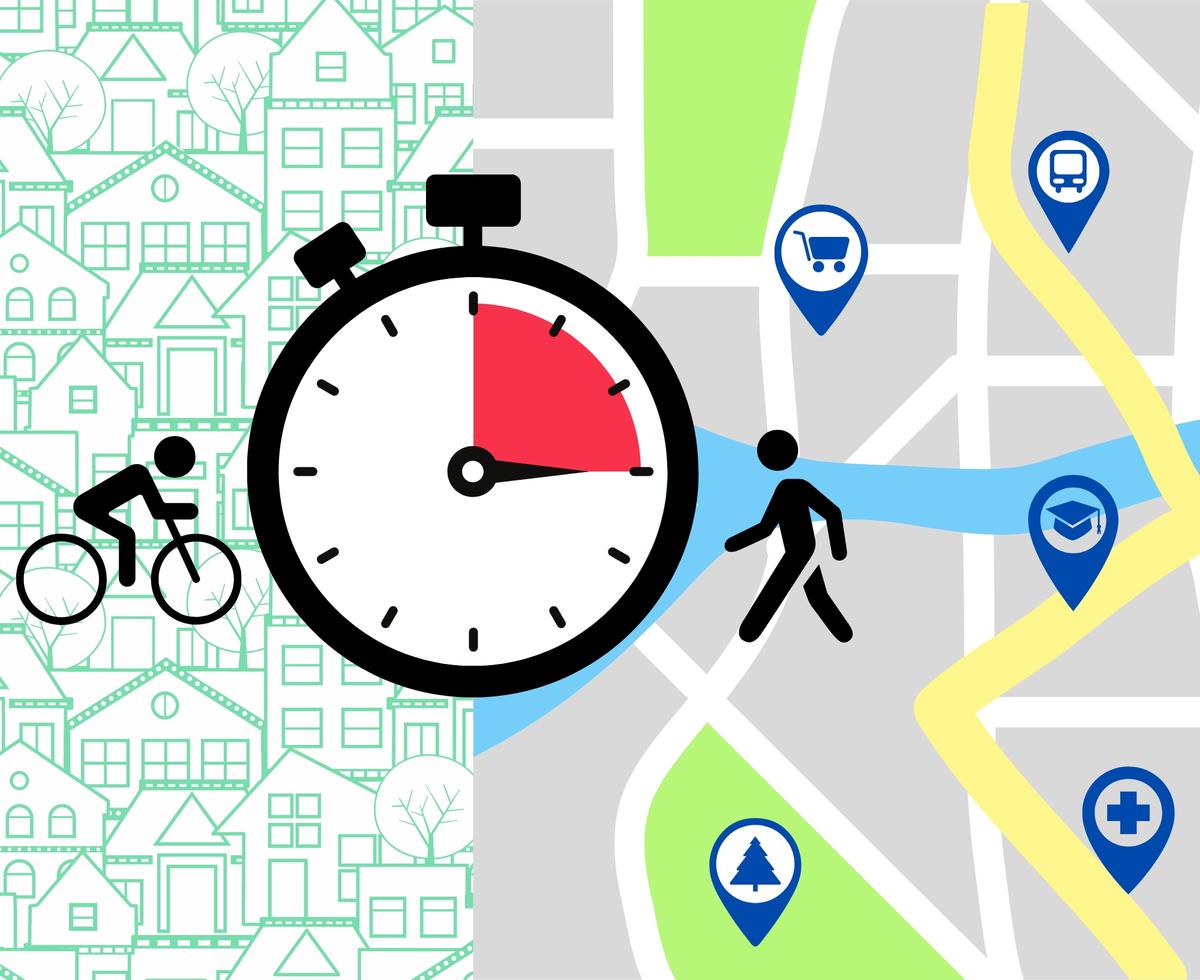

Will Bengalureans travel less and thus reduce the transportation load on roads if most of their needs – groceries, schools, healthcare, recreational avenues – are available within a 15-minute walk from their homes? As the city struggles to deal with its extreme congestion, water crises and unpredictable weather-triggered woes, can this 15-minute neighbourhood concept spark a much-needed turnaround?

Desperate scenarios call for desperate action, and this hyper-local model might just be a way out. “By ensuring that essential services, amenities, and opportunities are within a short walk from every doorstep, we can foster a sense of community, reduce reliance on cars, and improve quality of life for residents.” This articulation by Rakesh Singh, Additional Chief Secretary, State Urban Development Department, clearly maps a doable, workable rescue act out of the city’s inglorious urban mess.

Retro-fixing

But can retro-fixing work in a city that has gained notoriety for unplanned, unregulated growth, triggering unprecedented urban chaos? Many urban policy analysts are convinced that the 15-minute model fits the bill. “The concept addresses a key challenge in the planning process – tailored redevelopment of already-built, saturated cities to enhance the quality of life,” states the background note of the model’s comprehensive design guidelines prepared by Jana Urban Space Foundation.

The guidelines offer a structured roadmap to plan and implement the concept. To illustrate that it is workable, four city areas – Chickpete, Whitefield, Indiranagar, and Malleswaram – were selected as case studies. Distinct characteristics of each of these areas were identified: Primary land use patterns, population, built density, mobility patterns, availability of green spaces, public transit network, occupation, diverse socioeconomic backgrounds, and availability of land for development.

Targeted interventions helped identify the potential of these areas to transform into 15-minute neighbourhoods. The approach of the guidelines is to be flexible and complementary, providing quick wins through neighbourhood-specific proposals while addressing the gaps in planning and development. This is seen as significantly different from existing planning processes such as Land Use Planning, Transit Oriented Development, and Transport Planning.

Integrated mobility

Essentially, the guidelines are based on a framework of Move, Play, Sustain and Include. ‘Move’ is about integrated mobility and transport networks, accessibility and connectivity. The network here means non-motorised and public transport, safe intersections and organised utilities.

‘Play’ is about access to sustainable public spaces: parks, playgrounds and water bodies, designed to boost environmental sustainability and climate responsiveness. ‘Sustain’ implies access to local produce markets that promote sustainable farming and consumption patterns, reducing farm-to-table distances, and increasing economic opportunities.

By ‘include,’ the framework means integrating social infrastructure for the vulnerable and urban poor. This is achieved by building community halls, anganwadis, and safe spaces for girls. In fact, accessibility for ‘everyone at all times’ is the core principle of the 15-minute neighbourhood. To ensure that it works for all, it should cater to the needs of the most vulnerable groups: women, children, the elderly, people with disabilities, and the economically weaker class.

Do local residents feel the need for a 15-minute neighbourhood? A survey conducted as part of the guidelines process revealed that a high 69% consider transport infrastructure as the most important amenity required in their neighbourhood. While 61% did not find good quality transport infrastructure near their homes, their alternative was to either walk (40%) or cycle (8%) for short trips. Inevitably, 62% were forced to use private transport (29% two-wheelers and 33% four-wheelers) for long trips.

The hierarchy of commute, he reminds, starts with walking, followed by cycling and motorised transport, particularly public transport. Private transport should be the last priority.

| Photo Credit:

BHAGYA PRAKASH

Reliable transport infra

This perception, while acknowledging the need for new concepts, also raises questions. As independent mobility consultant Satya Arikutharam notes, “Without a reliable backbone of an integrated public transport and active mobility infrastructure, the concept would just be a pipedream.”

The hierarchy of commute, he reminds, starts with walking, followed by cycling and motorised transport, particularly public transport. Private transport should be the last priority. “But today, it is all reversed because the enabling infrastructure for walking and cycling is missing in Bengaluru. Anyone who wants to go to a park, hops onto a motorbike. They don’t walk because there are no walkable footpaths. Cycling is perceived as dangerous since they have to mingle with other traffic,” he explains.

Safer streets

To make neighbourhoods walkable, the survey had sought suggestions from residents themselves. While 47% suggested auto rickshaws and feeder bus services to transit points, 40% of the respondents had articulated the need for safer streets with better street lighting. Thirty-nine per cent wanted greenery and seating along roads, while 31% stressed the need for better traffic management at key intersections. More than half of the respondents sought a dramatic upgrade of pedestrian and cycling infrastructure in their neighbourhoods.

Though not structured or planned, the 15-minute concept has evolved randomly in some localities and gated communities. Satya cites the case of Electronics City, where housing units sprang up only 20 years after the place was developed. “It now has housing colonies close-by not out of design, but out of compulsion. People wondered why they should travel two hours daily when they could build a community there itself. However, the lack of enabling infrastructure elsewhere makes it suboptimal.”

Systems and frameworks can nudge the reconfiguration of the city’s neighbourhoods, says Bengaluru Apartments Federation (BAF) president Vikram Rai. “The city has exploded, having grown with a population of about 1.5 crore. While this is inevitable, frameworks can help optimise the neighbourhoods at the backend. Such an approach can guide and support future growth enabling decentralised local governance, local culture, and inducing a sense of environmental responsibility by shared ownership of neighbourhood lakes and more,” he elaborates.

Environmental benefits

From a walkability perspective, the 15-minute concept has clear environmental benefits: Improved air quality due to a shift from private cars to walking and cycling for short trips; and improved biodiversity by building green, walkable environments. The consequent reduction in fossil fuels for transport leads to a lowering of the urban heat island effect.

Besides the obvious health benefits, walkable neighbourhoods could also boost social interaction and sense of ownership of residents, encouraging them to be more involved in the community. Citing a report by the Institute of Transportation and Development Policy (ITDP), the Jana Urban Space study notes that women are more likely to engage in walking or cycling when streets are designed to prioritise pedestrian safety.

[ad_2]

Source link