[ad_1]

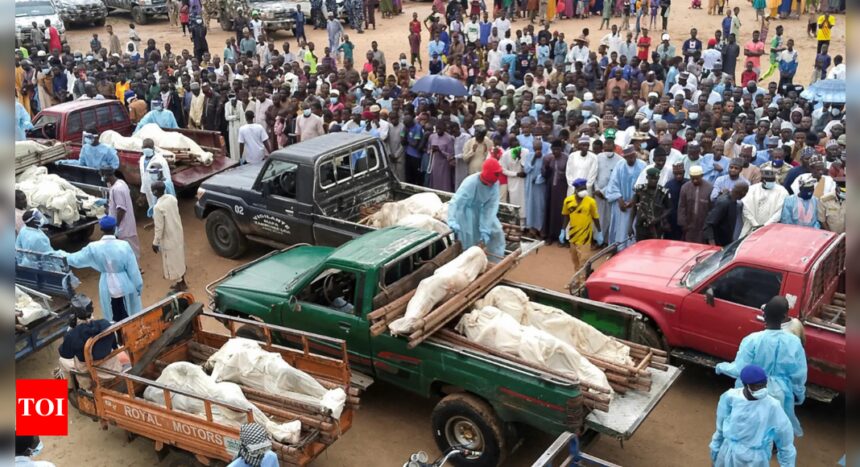

MAIDUGURI: At least 100 villagers were killed in northeastern Nigeria when suspected Boko Haram Islamic extremists opened fire on a market, on worshippers and in people’s homes, residents said Wednesday, the latest killings in Africa’s longest struggle with militancy.

More than 50 extremists on motorcycles rode into the Tarmuwa council area of Yobe state on Sunday evening and began firing before setting buildings ablaze, according to Yobe police spokesperson Dungus Abdulkarim.

The police blamed the attack on Boko Haram, which since 2009 has launched an insurgency to establish its radical interpretation of Islamic law, or Sharia, in the region. Boko Haram has since splintered into different factions, together accounting for the direct deaths of at least 35,000 people and the displacement of more than 2 million, as well as a humanitarian crisis with millions of people in dire need of foreign aid.

At least 1,500 people have so far been killed in the region this year in attacks by armed groups, according to the U.S.-based Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project, or ACLED.

Yobe Deputy Gov. Idi Barde Gubana gave a much lower death toll of 34 from Sunday’s attack. Contradictory statistics are a common trend in the security crisis, with the death toll from survivors’ count often higher than the official figure.

The 34 dead cited by the deputy governor were the ones buried in a single village, said Zanna Umar, a community leader, who said they have so far confirmed 102 villagers killed in the attack. Most of the others were either buried before officials arrived, or their bodies were taken to other places for burial.

“We are still working to search for more because many people are still missing,” said Umar.

Sunday’s attack is one of the deadliest in the last year in Yobe. The state is less frequently attacked than neighboring Borno, the epicenter of the war with Boko Haram.

Local media reported that the extremists claimed responsibility for the attack, saying it was in reprisal for villagers informing security operatives about their activities. A number of Boko Haram members were killed as a result of the information passed on by villagers, the militants were quoted as saying.

Reprisals are rampant in the northeast and villagers sometimes “pay the price” after military operations, said Confidence MacHarry with SBM Intelligence, a Lagos-based security firm.

“This is the first time our community has faced such a devastating attack,” said Buba Adamu, a local chief, his voice mixed with grief and fear. “We never imagined something like this could happen here.”

“There are some places (in the region) totally out of the control of the Nigerian army and villagers often live in fear of reprisals,” MacHarry said. In such places, he added, Nigerian security forces only go there for operations but do not have enough manpower to remain on the ground.

Nigerian President Bola Ahmed Tinubu, who was elected last year on a pledge to end the conflict with Boko Haram, condemned the attack in a statement that tried to assure villagers of justice but was silent about security measures.

Security analysts have faulted Tinubu’s security policies, saying he has not taken any bold steps so far to resolve the killings and that the problems he inherited, such as inadequate resources and manpower, remain.

More than 50 extremists on motorcycles rode into the Tarmuwa council area of Yobe state on Sunday evening and began firing before setting buildings ablaze, according to Yobe police spokesperson Dungus Abdulkarim.

The police blamed the attack on Boko Haram, which since 2009 has launched an insurgency to establish its radical interpretation of Islamic law, or Sharia, in the region. Boko Haram has since splintered into different factions, together accounting for the direct deaths of at least 35,000 people and the displacement of more than 2 million, as well as a humanitarian crisis with millions of people in dire need of foreign aid.

At least 1,500 people have so far been killed in the region this year in attacks by armed groups, according to the U.S.-based Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project, or ACLED.

Yobe Deputy Gov. Idi Barde Gubana gave a much lower death toll of 34 from Sunday’s attack. Contradictory statistics are a common trend in the security crisis, with the death toll from survivors’ count often higher than the official figure.

The 34 dead cited by the deputy governor were the ones buried in a single village, said Zanna Umar, a community leader, who said they have so far confirmed 102 villagers killed in the attack. Most of the others were either buried before officials arrived, or their bodies were taken to other places for burial.

“We are still working to search for more because many people are still missing,” said Umar.

Sunday’s attack is one of the deadliest in the last year in Yobe. The state is less frequently attacked than neighboring Borno, the epicenter of the war with Boko Haram.

Local media reported that the extremists claimed responsibility for the attack, saying it was in reprisal for villagers informing security operatives about their activities. A number of Boko Haram members were killed as a result of the information passed on by villagers, the militants were quoted as saying.

Reprisals are rampant in the northeast and villagers sometimes “pay the price” after military operations, said Confidence MacHarry with SBM Intelligence, a Lagos-based security firm.

“This is the first time our community has faced such a devastating attack,” said Buba Adamu, a local chief, his voice mixed with grief and fear. “We never imagined something like this could happen here.”

“There are some places (in the region) totally out of the control of the Nigerian army and villagers often live in fear of reprisals,” MacHarry said. In such places, he added, Nigerian security forces only go there for operations but do not have enough manpower to remain on the ground.

Nigerian President Bola Ahmed Tinubu, who was elected last year on a pledge to end the conflict with Boko Haram, condemned the attack in a statement that tried to assure villagers of justice but was silent about security measures.

Security analysts have faulted Tinubu’s security policies, saying he has not taken any bold steps so far to resolve the killings and that the problems he inherited, such as inadequate resources and manpower, remain.

[ad_2]

Source link